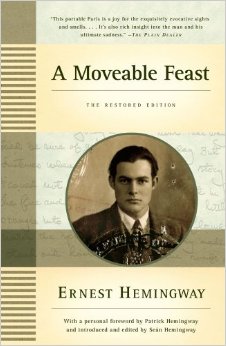

A Moveable Feast: A Lesson in Writing From Nobel Prize Winner Ernest Hemingway

Ernest Hemingway is best known as a novelist, but he started his career in journalism. For some time he was based in Paris, travelling Europe and writing for the Canadian newspaper The Toronto Star. It was here that he developed the concise, economical writing style that would win him the Nobel Prize for Literature.

Ernest Hemingway is best known as a novelist, but he started his career in journalism. For some time he was based in Paris, travelling Europe and writing for the Canadian newspaper The Toronto Star. It was here that he developed the concise, economical writing style that would win him the Nobel Prize for Literature.

A Moveable Feast is Hemingway’s memoir of those early days in Paris, as he made the transition from journalist to novelist. It features his friendships with Gertrude Stein, Scott Fitzgerald and Ezra Pound; his visits to Sylvia Bleach’s original Shakespeare & Company bookshop; gambling, cafes and ski trips.

The book inspired Woody Allen's film Midnight In Paris and gave me some ideas for my article about the city's creative heritage.

The book also contains thoughts about writing and creativity. I’ve always admired Hemingway’s direct and deceptively simple style. I’ve tried to emulate it, and it’s always made what I’ve written more powerful, so this book was educational as well as interesting.

The aim of this post is to draw out Hemingway's direct advice and thoughts on being a writer. I hope it helps - please write your own thoughts in the comments section, or Tweet me @AshBhardwaj.

How To Start

The book starts with a walk to a café, where Hemingway will write for the day. He evokes Paris with a few sentences about the cold weather, poor streets and the taste of oysters washed down with white wine. He talk of his routine:

“I always worked until I had something done and I always stopped when I knew what was going to happen next. That way I could be sure of going on the next day…”

And he muses on doubts and discipline:

“I would stand and look out over the roofs of Paris and think, ‘Do not worry. You have always written before and you will write now. All you have to do is write one true sentence. Write the truest sentence that you know.’ So finally I would write one true sentence, and then go on from there. It was easy then because there was always one true sentence that I knew or had seen or had heard someone say. If I started to write elaborately, or like someone introducing or presenting something, I found that I could cut that scrollwork or ornament out and throw it away and start with the first true simple declarative sentence I had written. Up in that room I decided that I would write one story about each thing that I knew about. I was trying to do this all the time and it was good and severe discipline.”

I learned a lot from this paragraph. It explains his method – and his belief in the importance of discipline - which contrasts with some characters in the book. He talks about getting himself in the right mindset:

“I learned not to think about anything that I was writing from the time I stopped writing until I started again the next day. That way my subconscious would be working on it and at the same time I would be listening to other people and noticing everything, I hoped; listening I hoped” and I would read so that I would not think about my work and make myself important to do it.”

Later, when he couldn't afford to eat, he says that paintings by Cézanne “were sharper and clearer and more beautiful if you were belly-empty, hollow-hungry.” He is talking about actual physical hunger, but he reflects on hunger driving him and how “Cézanne was probably hungry in a different way.”

He also says that he “was learning something from the painting of Cézanne that made writing simple true sentences far from enough to have the dimensions that I was trying to put in them.”

There are wonderful examples of his storytelling too. In Chapter Four he casts a dark premonition that’s almost painful. He describes a happy scene with his wife, which ends with, “’We’re always lucky,’ I said. And like a fool I did not knock on wood. There was wood everywhere in that apartment to knock on too.”

That final sentence, which seems so simple, adds layers of frustration, complacency and futility. For the rest of the book, each happy, loving scene with his wife tastes bittersweet to the reader.

Lessons:

- Treat work as a profession. Discipline yourself to write daily, and just to sit down and write one sentence. No matter how bad it is, it will get you started.

- If you don't know what to write about, just write something true; write about something you've done.

- Write simply, and reduce ornamentation in your writing. Cut back relentlessly.

Descriptions

Hemingway recounts his comings and goings from Paris. He talks about the time his wife lost his papers, meals in cafes, chicken in Lyon. And it’s all done using half the word-count of any other writer, yet more evocative because of that.

He talks of “my new theory that you could omit anything if you knew what you omitted and the omitted part would strengthen the story and make people feel something more than they understood.”

But he includes details that I would not think of. Of the garden near Montparnasse he says, “the horse chestnut trees were in blossom and there were many children playing on the gravelled walks with their nurses sitting on the benches, and I saw wood pigeons in the trees and heard others that I could not see.”

This type of sentence, which almost feels too long, is typical of Hemingway, adding one more thing than you would think of including: “with their nurses sitting on the benches”…. “and heard others that I could not see.”

He doesn’t describe what the nurses are wearing, or how the wood pigeons sounds, but it's enough to take you there.

Lessons:

- Write what you see and hear, nothing more. Don't over-describe.

- Paint the scene in a minimalist fashion.

Conversations

Hemingway’s conversations bounce back and forth like Vladimir and Estragon in Waiting For Godot (written by Beckett, who was also in Paris for much of his adult life) – the best of which is a conversation about social hierarchy with Ford Madox Ford. His conversations with his wife sound like scripts from old Hollywood movies, but they stand out as romantic and honest.

Hemingway the Apprentice

Hemingway makes the most of Sylvia Beach’s library, discovering new writers and learning from them. He says that “to have come on all this new world of writing, with time to read in a city like Paris where there was a way of living well and working, no matter how poor you were, was like having a great treasure given to you.”

He says Dostoyevsky and Tolstoi could be “so true they changed you as you read them; frailty and madness, wickedness and saintliness… the roads in Turgenev, and the movement of troops, the terrain and the officers.”

He is confused by Dostoyevsky because his style is the opposite of the lean style Hemingway uses – “he almost never used the 'mot juste' – the one and only correct word to use – and yet made his people come alive at times, as almost no one else did…. How can a man write so badly, so unbelievably badly, and make you feel so deeply.”

He talks this through with Ezra Pound, the man Hemingway “liked and trusted most as a critic, then the man who believed in the 'mot juste' - the man who had taught me to distrust adjectives.”

This is why Hemingway’s writing is so economical, and why it often took him “a whole morning just to write a single paragraph.”

Lessons:

- Study writing through reading - think about what different writers do, and their styles.

- Find friends and mentors who are practising writers and talk to them about what you've read.

- Find your style, but recognise that it's not the ONLY style.

- Try to find the 'mot juste' - the one true word for something.

Authenticity or refinement

Whilst on a road-trip, Fitzgerald tells Hemingway the story of his wife, Zelda, having an affair. Hemingway reflects on how refining a story dilutes its authenticity.

“Later he told me other versions of it as though trying them for use in a novel, but none was as sad as this first one and I always believed the first one, although any of them might have been true. They were told better each time; but they never hurt you the same way the first one did.”

Writing, drinking and discipline

The amount of drinking matches Hemingway’s legend, but it still seems a lot. He regularly drinks one or two bottles of wine over lunch or whilst reading a book in the park, although his “training was never to drink after dinner, nor before I wrote, nor while I was writing.”

It is through Hemingway’s friendship with Fitzgerald that he sees the problems of alcohol, for “anything that [Fitzgerald] drank seemed to stimulated him too much and then poison him.”

Hemingway appreciates the educational aspects of this friendship, such as when Fitzgerald “gave me a sort of oral Ph.D. thesis I Michael Arlen.”

We also learn about destructive forces around creativity, such as Fitzgerald’s wife Zelda who “was jealous of Scott’s work…. She smiled happily… as he drank the wine. I learned to know that smile very well. It meant she knew Scott would not be able to write.”

Lessons:

- Drink. But not too much.

- Be weary of saboteurs who will distract you from your vocation.

Some of my favourite quotes

“Everything good or bad left an emptiness when it stopped.” – Hemingway

“Anything you have to bet on to get a kick isn’t worth seeing.” – Mike Ward

“We need more mystery in our lives.” – Evan Shipman

“I felt the death loneliness that comes at the end of every day that is wasted in your life.” – Hemingway

Summary

This is what I took from A Moveable Feast on a single reading. Far more in-depth analyses have been done elsewhere, and I have steered clear of the controversies that surround it, the aspersions he casts on others, and the less savoury parts of Hemingway's character. Hemingway was no perfect role model, but his legacy on writing is immense.

To discover more of his writing style, start with the Old Man And The Sea. It's the short novel (you can read it in a train journey) that helpd him win the Nobel Prize For Literature.