Lessons in Leadership from General Stanley McChrystal

Gen. Stanley McChrystal, when photographed for Time magazine

Something a bit different today.

Last month, I went to a talk by the retired American General Stanley McChrystal. McChrystal had commanded JSOC (America’s Joint Special Operations Command), before becoming the commander of ISAF (the International Security Assistance Force in Afghanistan). He was the pre-eminent soldier of his generation, but lost his job in 2010, when members of his team made unflattering remarks about members of President Obama’s administration, to a journalist from Rolling Stone magazine. Realising that he had undermined the leadership of the President of the United States, McChrystal resigned. Since then, he has taken up a post at Yale University, teaching international relations, and written three books. Leadership is the theme that runs through all three of them.

Leadership is a nebulous topic, and it is one that McChrystal has made it his life’s work to study: first as a soldier, and then as an academic, author and consultant. The rest of this blog post comes from my notes taken during MChrystal’s conversation with Hanna MacInnes of the "How To Academy, at Conway Hall, Red Lion Square, on November 7th 2018. Their conversation was centred around Leaders: Myths and Reality; his third book, exploring leadership and all its complexities.

Leadership affects all of us, whether we are followers of leaders, or leaders ourselves. So I thought that it would be worth sharing my notes from the talk. Quotation marks indicate direct quotes from General McChrystal himself.

1. BACKGROUND

As a student and soldier, McChrystal learned and practised leadership. The intent of his first book, his memoirs, was to write a triumphal book on the subject. He did interviews with others who had lived under his leadership, and discovered that his own memory of key events was incomplete - his perspective and memory did not match theirs. He realised that others in his team had a lot more to do with output from his leadership than he had previously thought.

Team of Teams (his second book) was based on his experience in Iraq, leading a team made up of many other teams. Upon the book’s release, he discovered that his own experience was similar to that of many businesses, and he realised that he knew leadership incompletely. He had been a leader in the military for 32 years, and been teaching leadership as a consultant for 9 years. So he went back to Plutarch, the Roman writer about leadership, as a starting point to unravel his own confusion around the topic.

The other goal was to start a national conversation about leadership above politics and tactics: what do we (as followers) want from our leaders?

2. THE BOOK:

The structure is based on 13 individuals, (6 pairs and one individual). This followed the format of Plutarch’s books, which explored and compared the parallel lives of 48 Greek and Roman leaders. McChrystal did 6 pairs. The individuals in the pairs were not alike, but had similar themes for why they emerged as leaders, and allowed McC to ask the question of why they emerged as leaders.

Robert E. Lee

3. ROBERT E. LEE

The Confederate US Civil War General was the biggest example of positive leadership that McChrystal tried to emulate in his life. Lee is venerated in America today, particularly in military circles, and McChrystal always felt a strong connection to Lee. Lee grew up near where McChrystal did, in Virginia. Lee went to West Point and served 32 years in the US Army, as McChrystal did. McChrystal went to Lee high school and lived in Lee barracks; Lee was a beacon to look up to, and was considered too good to try to emulate, but someone to aspire to be like. McChrystal had a painting of Lee, given to him by his wife as a wedding present, and McChrystal hung it in every place he lived.

In the spring of 2017, there were racist, white supremacists activities in Charlottesville, Virginia, over the removal of a Lee statue. McChrystal’s wife told him that he had to take down the picture of Lee. His wife said that it would communicate something unintentional, that people coming to their house would think that he supported white supremacy. It was an emotional, visceral connection for McChrystal, but he threw away the portrait and reconsidered Lee.

Lee had all the qualities and experiences that soldiers admire. But when he sided with the Confederates in the Civil War, he broke his oath to the United States. He did it to protect slavery (“the greatest evil in American history”) and to destroy the United States, which George Washington had done so much to protect. Lee was a man, a flawed man, who made a big mistake. McChrystal chose for him to stand alone in the book as a study and lesson on leadership.

4. BOOK THEMES

a. The Three Myths of Leadership:

As a child, McChrystal read lots of Greek and Roman history and legends. He remembered the story of Atlas, holding up the sky, and realised that people used myths to explain what they didn’t understand. Eventually, that myth becomes a sort of truth, and people just accept it. The same is true of leadership. Over time, different myths have grown up to explain leadership, and now they are just accepted as truth. McChrystal has, in the past, been guilty of believing these truths. They are:

1. The Formulaic Myth. The mistaken belief that, if you follow a certain formula, you would be a good, successful leader. Many leaders have all those traits in spades, but they fail. Lee had a lot of the classic leadership traits, and he still failed

2. The Attribution Myth. The mistaken belief that success and failure of an organisation is down to the leader

3. The Results Myth. The belief that we only follow leaders who win. We demand results-oriented leaders, but actually, we follow leaders that fail a lot. This is because leadership is an emotional interaction, not just KPIs. It is a thing that occurs: like an emergent property from a chemical reaction

b. Women in Leadership

The existing gender balance in leadership is disturbing and unhealthy. In the US, there are more CEOs named John than there are female CEOs in total. This is historical, too, so there’s less track record of woman in leadership, and thus less to study. For those that have risen to lead, their stories document an improbable rise to success. As such, they are particularly important to study. In the book, McChrystal looks at:

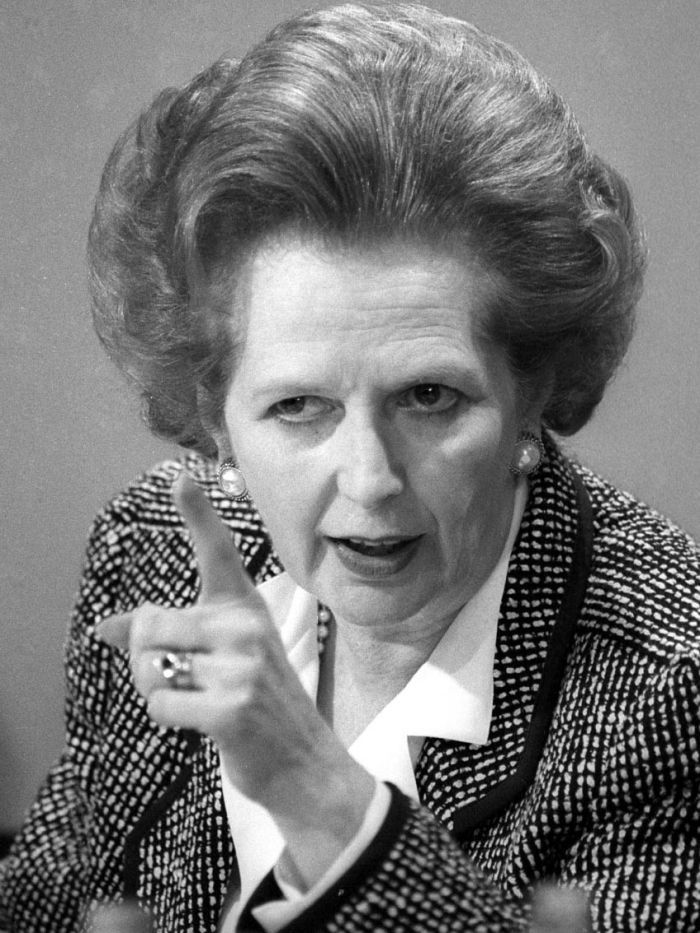

Margaret Thatcher

1. Coco Chanel. She was bright and opportunistic. She saw that a change was necessary in fashion (lighter, form-fitting, not uncomfortable). Then she lived the brand.

2. Harriet Tubman. An escaped slave who went back into slave territory 13 times to lead people out. She became a spiritual symbol for the anti-slavery movement.

3. Margaret Thatcher. A grocer’s daughter, who had to take vocal and behavioural coaching in order to seem less female in demeanour, in order to succeed in a world that prejudiced masculine characteristics.

All women that have succeeded have had a harder road to the top than any man. Better opportunity must be provided for women to succeed. This isn’t just for reasons of social justice: Businesses perform better when they have greater diversity. The companies with more women and ethnic diversity on their boards make more money. You don’t argue with data..

c. Charisma

1. Many leaders were charismatic, but they weren’t all charismatic in the same way. Robespierre (the leader of the French revolution) was a poor speaker, but he came with a sort of zealotry from his conviction. There were some people who opposed the direction he was going, but he was unwavering and firm in his conviction. That made people think that he must have something, and so they followed him.

2. Al-Zarqawi was the leader of the Zarqawi network in Iraq; Islamic insurgents who swore fealty to Al-Qaeda and fought the US occupation troops and the US-backed Iraqi government. Al-Zarqawi was the primary target of McChrystal’s efforts during his time as JSOC commander in Iraq. To his followers, Zarqawi had a sort of charisma through the fervency of his belief: he personally beheaded an American on video in Spring 2004, and he looked like a thug, but he was so focused on his mission. He led patiently and (according to McChrystal) bravely. People didn’t necessarily have the same fervency of belief that he did, but they were captivated by him.

d. Communicators and Decentralised Command.

Martin Luther King

In August 1963, Martin Luther King gave his “I have a dream” speech to 250,000 people in Washington. He had been up until 4am the night before, writing it. When he delivered it, the first 11 minutes didn’t work - the crowd listened politely, but unenthusiastically. Someone stood next to him realised this and, knowing how well King could captivate the crowd, told him to throw away his prepared speech and speak from the heart, to tell them about “the dream”. King did so, and gave one of the greatest speeches in history.

At that time, King had been in the movement for 8 years, since the age of 26. He organised a movement to avoid African Americans using public transport, in order to stop segregation. He was never elected and moved around the South organising groups of many strong-willed and experienced civil rights leaders. And he didn’t just sit in an office giving commands: he lived it and empowered other leaders.

1968, Martin Luther King was murdered. after 13 years at the head of the movement. But the movement did not collapse, because he had created a movement with momentum, with localised leaders, that could outlive him.

Through communication, some people emerge as leaders unintentionally. In 1923, Einstein was the most famous man in the world. He communicated constantly through his community, connecting people, giving other young physicists opportunity. He was a symbol, rather than a practical leader, but was offered the presidency of Israel (he turned it down). His symbolic leadership came from his ability to communicate.

e. Are There Born Leaders?

Many are born with the traits and tools that will help, but leadership itself is earned. It starts with the templates that you are exposed to when you are young: parents, teachers and other direct experience. Most that become leaders start with being given some responsibility at some point, where something has to happen. This can be in sports teams, or class, or even in the family, where they have the chance to practice the muscle of leadership.

In combat situations, we sometimes encounter “informal leadership” in which a Rifleman or Private demonstrates the ability to direct, assess and inspire, that is beyond his rank. That informal leadership is not “born innate”, but has come from somewhere. It usually goes back to experiences when they were younger, such as captaining a football team, and now it is being expressed.

4. QUESTIONS

After talking about his book, McChrystal was asked wide-ranging questions on leadership, politics and his life by the interviewer and audience.

a. Is Trump a good leader?

“You cannot deny that he is effective. He is a business guy who got elected. But good is separate to effective, because that is a value judgement. Trump is effective in terms of winning, but he is not a good leader for America.

“He has pulled things from inside us that are not good, and stimulated things that are not good. He has caused emotions and behaviours that are counter to the American character. His inability to stick to the truth is not what we would want from our children. He has been a negative leader.

“When will the people of America start to look in the mirror and question their values and the kind of leaders that they want for their nation? That’s part of the reason for the latest book.

“From a political point of view, for Trump, the mid-terms are good because it gives him someone to blame (Congress) if he does not achieve things. But the increased engagement and voting shows people are listening and starting to decide. Also, there are now more women. Once you reach a critical mass of women, the dynamic changes.

“The electorate want female politicians to be a man. For them to succeed, they will need proven competence over time, and even that isn’t always enough. Clinton had proven competence, but she came with other baggage that prevented her election. Her opponent didn’t have any proven competence in the field.”

b. Is Foreign Policy in America changing?

“Foreign Policy is supposed to be consistent in the US, never mind who the President is. But that has changed in the last few years, first under Obama and then Trump, so Obama is not above criticism. But the tone under Trump is much more damaging than the policies and choices that he has made.”

c. Should we continue to be in Afghanistan?

“I’m not the right person to ask that question of, because I’m biased and I like the Afghans and the Afghan people. I’ve seen the girls going to school and I met Afghan soldiers who want to serve their country, even when they are heavily wounded. From a distance it looks like the graveyard of empires, etc, but when you get up close it looks like people. It looks like possibility.

“I took over JSOC in 2009, when the war was 8 years old and everyone had lost interest in it: Americans had lost interest in it. Pakistanis had. The Afghans had, our Allies had. Everyone thought Americans would leave, but the mission had not changed. So we had to change the lack of confidence: to believe that we could, should and would win. “

d. “Did you have to believe in the military strategy yourself?”

“Whilst the mission remained the same, the strategy needed to change. But even then, I believed that it had a 50/50 chance of success. As a 3 or 4 star general you are obliged to give your true opinion to the Senate, no matter what the administration says. But, as a 4-star general, your audience is not just the Senate. It’s also your soldiers. So you can’t say “maybe we could win,” because then your soldiers will doubt the entire campaign, and then the campaign would definitely fail.

“You have to show confidence and conviction, or you guarantee failure. Did Henry V believe that he could win the Battle of Agincourt? Well, he told the soldiers, that he believed they would win. If he had not said that, he would have definitely failed.”

d. “What happened with the Rolling Stone article?”

“It was supposed to be a puff piece about the command team of ISAF. But, when it came out it was titled “Runaway General”, so we quickly realised it was not a puff piece! The article put a contentious issue on President Obama’s desk, and my job was to stop contentious stuff ending up on the President’s desk.

“I immediately offered my resignation. I regret the incident and that it had happened. In an instant, I lost a career that he had been working at for 38 years; something that I had done since the age of 17. Every other thing that I had done well, as a soldier, counted for nothing, and was subsumed under “disgraced general” “fired general”. But I accept the responsibility for messing up, just as I accepted the accolades for the good stuff that I did in my career.

“When you fail at something you have two choices:

i. Continuously relive it (as the disgraced or angry person).

ii. Live life forward. You can’t change what happened in the past, so don’t worry about it.”

e. “How do you deal with failure?”

i. “Except for one bad day (and it was a very bad day) I have had a great life. But failure has been integral to that.

ii. “You are going to go forward and try to lead, but you will, sometimes, fail.

iii. “The best batter in baseball history failed 60% of the time. You even if you are good, you will fail as much as you win. You can do everything right and still fail. But failure is not a sign of being a bad leader.”

f. “What do you see as the future of leadership? Are we in the age of the follower?”

“No, we are in the teen-age, and the idea of the single leader is a bit past. Decentralisation of leadership and mission command, a more diffuse leadership, is absolutely key and important, particularly because of changing technology and connectivity. Leadership requires skill AND adaptability. Leaders need to go into entirely new environments and feel the people around them. And grow. Unfamiliar tasks are important.”

g. “How does leadership differ at different levels?”

“Vince Lombardi adapted how he coached at each level. The way you coach an NFL team is different to coaching a high-school team, or an academy team.

“As you go up the levels in an organisation, you have less knowledge about what’s happening in an organisation. You are not close enough to the sharp end. In the military, the rank of “General” actually means a “general officer” as against a specialist within your branch of the Army. To counter this ignorance, we need to be more curious about what our force or team knows, and be able to say “I don’t know,” and not worry about admitting that. Show some reality.

“I waver on showing vulnerability, though. Although you need honesty, you don’t want people to lose confidence in you.”

g. “Should there be women in ground close combat?”

“The argument had already been made and won on the ground, because women were fighting on the front line the entire time in Afghanistan. Experience has shown that it works, but it is still good that policy has caught up with reality

“It was the same case with gay people in the military. The Americans had a policy called “don’t ask, don’t tell” in which you would be kicked out if you were found to be gay. Backward members of the military said that ‘gay people would undermine the military’, but it was against regulations to ask someone if they were gay, and also against regulations to tell someone you were gay.

“Of course, there were plenty of very good gay soldiers in the Army. And those same people who didn’t want gay people in the army would say, ‘Gay people undermine the Army. But not xxx. He is an exception. I know he is gay, but he is really good and I need him in my organisation.’

“So the argument was shown to be completely idiotic because there were always gay people in the Army, and the Army performed perfectly well. It’s a similar case with women.”

h. “How do you give authority to your subordinates (mission command)?

“Leaders must know that things will happen at the edge of their organisation that are too fast to control. So intent and mission command must exist. Direction is passed on, and decisions made within that. The problem with good information command is that it tempts you into micromanagement.

“How do you overcome information flow? Create more time: limit emails; no one-on-one meetings; let people self-curate which information they deem necessary to complete their task.

“When I ran JSOC, the team created four information levels, and sent out daily briefs. At the top of the brief was push-information: a headline that everyone saw, so they knew the key information, and intent of the day’s operations. All three levels below that were pull, and everyone could dig in for more information if they needed it for their task, but it was not forced upon them. This prevented them being overwhelmed with information that did not help them complete their task.”

i. “What was the mission statement in Afghanistan?”

“To Protect the Stability, Existence and Sovereignty of Afghanistan in order to prevent it becoming a state re-occupied by Al Qaeda or another terrorist state.

“This needs to be remembered in all questions about Afghanistan, and shows why it must be an enduring mission. Things change on the ground, but you must not let that change the mission. But you must consider the tactical.

“The strategic without the tactical is academic. Good leadership is constantly refining the tactical and strategic, at the same time.”

McChrystal with President Obama

5. SUMMARY

It was great to listen to someone who had lived and breathed leadership at every level, from the front line to the national strategic level, and everything in between. To see that someone so experienced in leadership could still be so humble and curious about its nature was reassuring. It certainly gave me a lot to think about when I lead in various aspects of my own work.