Through Soviet Shadows: A Journey from Norway to Romania

"Cultural exploration" in Estonia. Wearing a Soviet admiral's uniform.

Last September I went to Estonia with the British Army. Between digging trenches and running through forests, I had time to explore the nearby villages and even get to the capital, Tallinn, with our Estonian colleagues. As always, I was delighted to discover a new country, but what struck me most was Estonia's complex history and identity.

I hadn’t known that Estonians consider themselves Scandinavian, or that a quarter of their population was Russian, or that Estonians had fought for Germany and the Soviet Union during World War Two. And that the German defeat led to Estonia becoming part of the Soviet Union.

The very nature of this event is contested: Russian-speakers call it liberation from fascism; Estonians call it occupation. Even independence in 1991 didn’t bring an end to the Soviet legacy: communities were literally split in two and formerly secret towns, with entirely Russian populations, permanently altered Estonia's demography.

I realized how ignorant I was about eastern Europe. I knew of the countries along Russia's border, but I knew little about them: How did Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania differ? Was Poland just full of plumbers and waiters? Wasn't Belarus part of Russia? Was all of Ukraine a warzone? Where exactly is Moldova?

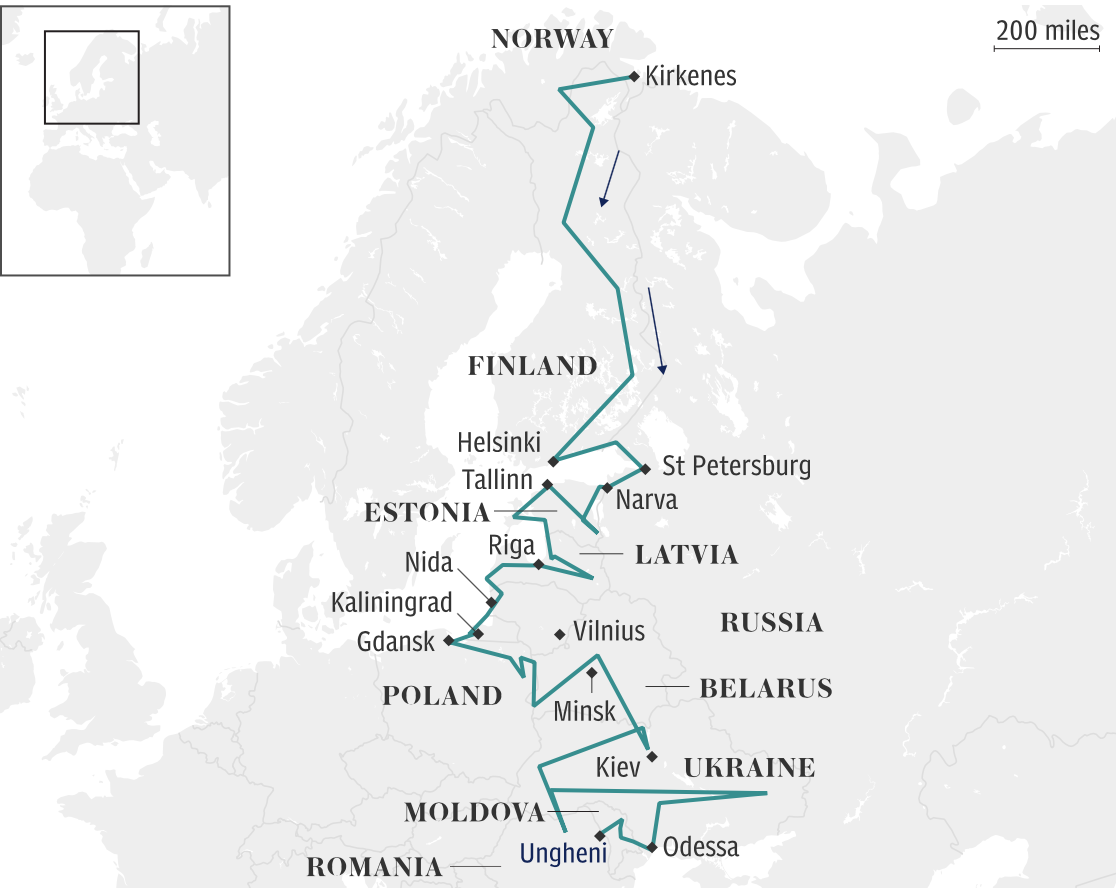

The route: Arctic Norway to Romanian summer. Image by The Telegraph

As I looked at a map, I saw a line of questions along Russia’s border with Europe: the places in between - often far from national capitals - where identity means everything. I imagined whizzing along this line, as the sounds of language altered with the landscape, and architecture changed with the cuisine.

We think of nations as hermetically sealed: on this side you speak French and love wine and cheese; over there you wear lederhosen and love bratwurst and beer. But the world is not like that: cuisine, language, loyalty and memory are not as neat as geography. They move with people, who cross borders for love, for work, or sometimes war and conquest.

The world is not as simple as demagogues would like us to believe, so I decided to explore those places in the liminal space between east and west.

I would start in Arctic Norway, at one end of the old Iron Curtain, heading south through Finland and St Petersburg. After that I would travel through the Baltic states of Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania and Kaliningrad - an exclave of Russia that used to be Prussian. Then to Gdansk in Poland, across to Belarus, down to Ukraine and through Moldova, finishing at the Romanian border.

All of the countries I would pass through had a border with Russia, except for Moldova. But Moldova had a breakaway region backed by Russia, and I wanted to learn something about the least-visited country in Europe (In 2017, Moldova had just 11,000 international visitors. For comparison, the UK had 40 million).

Flying into Norway. "Crossing the boundary between home and adventure."

I wasn't setting out to do current affairs or news. I would go as a traveller, to discover what I could about the places I passed through and the people that lived there.

The journey would cover 8500km, starting in the Arctic winter, and finishing in the Carpathian summer. I would walk wherever possible, and use local transport whenever else. Pillaging my social networks, I found a chain of friends and acquaintances who would pass me along the route, helping me ease my way into each culture.

Crossing that boundary between home and adventure is always a special moment. Those towns with funny names that existed only on a map, and people who exist only in emails, suddenly become solid and real. The roads and paths solidify beneath my boots; and home fades into memory, burning bright with nostalgia.

And there’s the knowledge that, no matter how much I research, it will never be as I expected. Oh, I can know what a Norwegian fjord looks like from photographs; but I can’t imagine how it feels to be there in winter, with the cold air rushing into my lungs and the the inky blackness of the water looking infinite against the white mountains.

This is why we travel, why we overcome doubt about it being a good idea and shedding the comfort of loved ones and familiarity. To know what it feels like. And to cast oneself onto chance and fortune.